22. My 1st Area: Monterreal, Rio Bravo

- L Rshaw

- Aug 25, 2019

- 12 min read

Updated: Nov 13, 2022

"In learning you will teach, and in teaching you will learn"

--- Phil Collins (Drummer, Singer, Songwriter; 1951 - Present)

First of all, I am very grateful for the family who put up with so many missionaries coming and going upstairs. I know that missionaries weren't always the best neighbors to have to share the premises and some commodities but they were always so good to us and always took care of us like family. Again, much of my amazement is by no means meant to be insulting, merely the remnants of impressive culture shock as this was my first home in Mexico, not knowing anything or anyone. That's why I remember it with all my senses.

Click to Navigate (Table of Contents):

FIRST FRIENDS

We departed by bus from Reynosa to Rio Bravo. Elder Howard knew what he was doing (See "Trainers and Testimonies"). We started getting to know each other immediately seeing as we'd have nothing but time together every second of the day. He distracted me from my quiet nervousness by asking me questions about myself as soon as we got on the bus; it's not an easy thing for an introvert like myself to open up all at once. All I could think about was home. Seven hundred long days away. Would I make it? Elder Howard and I became fast friends and I had to confide in him. I had nothing to fear because we would help each other. I wasn’t expected to know or do everything at once. All that was expected was that I do my best to learn bit by bit. And I certainly endeavored to.

Before I knew it, we arrived in the small city of Rio Bravo (granted, only small compared to most major cities but not small itself). Certainly, walking from place to place made it feel enormous as there were no taxis and the only shuttles were deeper into downtown away from our designated area.

As per custom, our Zone Leaders were there waiting for us (See "Mission Administration"), Elder Adams and Elder Saldaña, both of which were in the "latter days" of their missions. I wasn’t much of a conversationalist back then but I opened up a lot better when I found out that Elder Adams’ grandparents lived in my Ward back home in Utah! ("Ward" being the term for a local congregation). They'd been friends of the family for years! What are the odds that we would meet in Mexico, in little Rio Bravo of all places on Earth?! And that he would be my Zone Leader whom I'd see a few times a week?! I think God was telling me from the start, if it weren't already evident before, that He was still very aware of me wherever I went. I didn't feel like I was among complete strangers anymore and I'd only just arrived. When his grandfather, Dave Weidner, passed away a few years later, I saw Elder Adams again at the funeral in the very same chapel that I'd attended almost my whole life. I saw him again at a wedding a few years after that. And it took a tiny city in Mexico to bring two Utah locals together.

Elder Howard explained that we lived above one of the Branch President's counselors, Hermano Peña. (See "Church Organization"). It was him who picked us up from the bus station in his aptly-called pickup truck. I sat in the back seat while Elder Howard had a conversation with him in Spanish about who-knows-what in the front. I could pick out a few words here or there but most of it flew over my head. But neither did I interest myself in their conversation, to be honest. I was content to get my first look at Rio Bravo passing by my window. The restaurants, the movie theater, the pharmacies, the department stores, and the shops; the only time I would see them was on route to the chapel or the Zone Leaders’ house, each of which happened about once a week. Otherwise, our area didn’t include any of that stuff. Our area was practically one hundred percent residential.

THE NEIGHBORHOOD

“Barrio” (Bah-rryoh) is a Spanish for “neighborhood” but also means “Ward” as in "a local congregation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints".

Rio Bravo didn’t have enough Church members to constitute any Wards, but it did have four Branches and two meetinghouses (See "Church Organization"). The Spanish word for "branch" is Rama. A Branch is like a smaller version of a Ward. Three of the four said Branches shared the same chapel building in the center of the city including the Branch I was assigned to, the Monterreal Branch, then the Rio Bravo Branch, and the Madero Branch. The other Branch, another mile East through the city which had its own tiny chapel building, was the Condesa Branch.

Even though the Spanish word for "neighborhood" is barrio, the word that was used by everyone was colonia. If you wanted to know where a place was, you ask them what the name of the "Colonia" was.

For the duration of my time as a missionary, because we weren't allowed smartphones (back then), the only navigational resource was had was paper maps, word of mouth, and personal experience. In most cases, because I was never the first missionary to live in an Area, most of the maps that I had were maps that I inherited from previous missionaries. In many cases, the maps were old and worn and sometimes ineligible. Some were large and were best left on the wall for all to share. Others were small enough for each companionship to carry with them throughout the day. If we didn't have a map on our person, it was necessary to go get one. Paper maps were surprisingly hard to come by, at least accurate detailed ones.

Each neighborhood, colonia, vicinity, had such a distinct feel from one end of a city to the next but it’s hard to pin a finger on why that was. Other things were the same everywhere you went. For example, one difference that I noticed in Rio Bravo that differs from Reynosa is that there is much more use of wood and tin. And instead of iron gates, there are more fences, both wooden and chain. Monterreal was noticeably greener than Reynosa; like a town that a jungle had grown on top of which would have been nice in the summer had I been so lucky. There was far more diversity in the structures and they were generally smaller too; even shack-like at times. Some looked so small and poor that you'd wonder if anyone lived there or not.

The Mexicans were huge into fiestas and celebrated anything and everything whether it was a birthday or if their child was graduating preschool. Cake to go around. Celebrating long into the night. Alcohol was often involved. If it was warm enough, you might smell sausages or carne asada sizzling on the grill. And what would a fiesta be without blasting music as loud as possible?! Seriously though, if there was a fiesta, no one in the neighborhood would get any sleep.

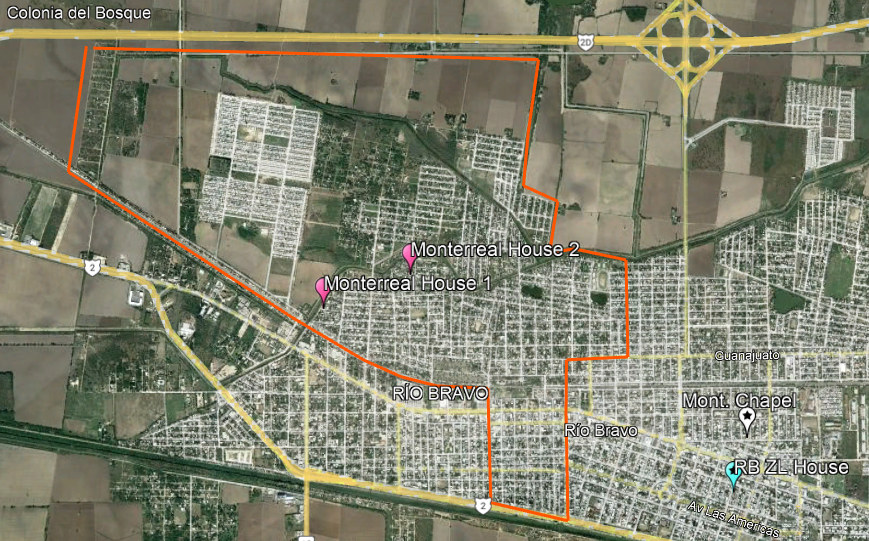

We lived pretty dead center of the Monterreal area but we worked mostly in the northwest where it seemed that there were more people due to new developing neighborhoods but to get there we had to cross the train tracks. If I were a wiser more experienced missionary, I would have tried the lesser-known streets to the East more. We’d hear the loud train almost every morning during study hours since the tracks were only about two streets south of us. The tracks doubled as a bridge to the other side of the smelly canal to avoid walking the long way around; most everyone preferred this path of convenience over the safer one. So long as you were cautious, there was little danger taking this shortcut. If you wanted to, you'd continue going straight from here to the main road and pull a U-turn back to the other side of the canal but that probably would have taken at least 10 minutes longer.

Local businesses were small. Crossing the bridge led to a small produce shop, a sort of farmer’s market, a home turned barbershop, an auto repair garage with old tires and rusty car parts out front, and one-story houses. Sometimes we’d have to cross vast fields in order to reach the next neighborhood. It varied from place to place. Never entirely urban but neither rural, always somewhere in the middle. Considerably poor communities, lots of dirt or rocky roads, wild grass anywhere it could grow, wooden fences and cinder walls, occasional tin roofing, and minimal shade.

The rain made life muddy; otherwise, everything got submerged in water anywhere from the ankle to the mid-calf. I kid you not, the streets could turn into rivers. The water had nowhere to go because of a general lack of rain gutters. It simply traveled from high to low ground, as water does. Puddles collected in the dips and deep potholes of the streets until they could evaporate into obnoxious summer humidity. A combination of rain, the canal, mud, and the time of year made for armies of mosquitoes.

I still remember pulling up to the house for the first time. It sat on the corner of a dusty light gray street that ended in a dirt road dead-end just far enough away from the wide stagnant green canal (I mentioned three paragraphs before) that reeked. Along that canal grew many tall types of grass and a few trees, which blocked the greater view across the canal. All along and beside the canal was usually a mound of garbage that neighbors burned every week or two since the garbage pickup system was virtually non-existent in that area. At times, we would return home at night to see the garbage heap turned tall bonfire throwing up ash flakes. When it would rain, the dirt road would turn into mud that absorbed much of the garbage and crack and harden again in the sun which made it an incredibly bumpy and shapeless minefield that was easy to twist an ankle on if someone wasn't vigilant, especially walking home at night. Imagine walking home in the slippery mud hills in the dark when it's raining!

THE HOUSE

The house was decent while small and simple. The two of us shared the equivalent space that the entire family of four beneath us did but if they made it work between the four of them, we could make it work between the two of us.

To enter our apartment, we had to go around the back and up a concrete staircase (even not having a railing to hold onto was a bit unnerving at times, especially coming home at night). Our place didn’t have much in it. The first room had two old wardrobes to hang clothes (on top of them were heaps of old dust covered magazines and junk items that previous missionaries had left behind), a white speckled foldout table covered with plastic dishware, and a fridge about 4 feet tall with nothing but old condiments in it and near-empty cereal boxes on top (not unlike the mission home).

I don't know why but there were about two or three inches of elevation gain between the main area and the other rooms of the house where the bedroom and study room was which meant you really had to watch your step or you could easily trip (which happened on multiple occasions).

Our study room (which was to the back and to the right) had another similar fold-out table shared between the two of us and our rotting termite-infested bookshelf for our pamphlets that left black crumbs on the floor. We even had stacks of old useless paper materials that had been left there for many moons. The study room had a door that led outside to a "patio" area with a delightfully comfy hammock suspended between two white pillars that supported a small roof area (We'd often leave this door open to let the cooler morning air in while we studied). The "patio" had no railing and doubled as the roof over which the truck was parked.

I was warned to always wear sandals around the house. Not only did it pad the soles against the hard tile flooring, but sandals were also a sanitary measure. You never knew what was on the floor. I heard stories of more than one person spreading athlete’s foot carelessly. Things happen when people are always on their feet, especially if you don’t use clean dry socks regularly (which was never a problem I had but I went through a lot of socks wearing them out until they were paper thin and holey). Whenever I wasn’t wearing shoes, you could bet that I was wearing my black sandals, whether in the house or in the shower. It felt strange wearing sandals indoors in the beginning but it was weirder getting used to being without them after the mission.

Because of the rocky cinder-block makeup of the buildings, the inside temperature largely depended on the weather outside because the solid walls had no insulation. If it was hot outside, it was hot and muggy inside. If it was cold outside, it was wet and freezing inside. Because the walls were usually solid stone (with the exception of plumbing and electricity), there were no vents and so there was no central air conditioning. You could buy an air conditioning unit called a “clima” (clee-mah) that you'd mount on the wall but it was expensive and would spike the power bill. At times in the mission, we were fortunate to have a clima for the night hours but we didn’t at this time. I guess it was just more incentive to get out of the house and work. Whenever possible we left the windows cracked. Elder Howard and I were amazed once to come home and find a good-sized bird that’d snuck into our house through the torn mesh on the window by our front door. After dancing with it, we were able to scare it out the door.

Our bedroom, just opposite of the tiny study room, was small and kept cool only by two standing fans, one of which had no protective guard whose silver blade would spin dangerously near my face as I slept; the other seemed to be tied to Elder Howard's bed towards the feet by bungee cords. We slid the window open to get the air flowing through the slow cooker house, except in the winter when it was a freezer. Our blue bed sheets added color to an otherwise predominantly white and gray room. Our beds were low to the ground and covered by what little we cared to place on it in that initial heatwave, including the gray king-sized furry blanket President Morales gifted us in preparation for winter. That blanket was comfortable but a hassle to transport. The only other piece of furniture (if you want to call it that) in our bedroom was an ironing board that had been burned through which we often used as a stand to put things on. Even then, it blocked the door a bit. So, all in all, our bedroom only had two beds, two fans, and an ironing board. At night, we'd plug our archaic blue phone in to charge, set the obnoxious alarm for the morning, and set it on the hard tile floor.

We had two small bathrooms, both of which used water that flowed from a large water tank that sat on the roof carried by gravity. The shower water ran from a metal pipe that stuck out of the wall with absolutely no water pressure and had only one temperature setting that reflected the weather. The shower was absolutely disgusting because the water pressure was so low, that the escaping water would only fall a few inches forward, smack the ground with all the grace and sound of a belly-flopping waterfall and miss the whole of the basin so you'd have to get up really close to the pipe. All the dirt runoff would literally just sit on the floor and in the corners of the rippled ground out of the reach of the smacking waterfall. The humidity didn't help. Mopping helped some but it was a lot of work and time to have to constantly be mopping. Most of my memories in that shower were of icy cold water. I'll talk more about what we did in the cold weather in another post.

We had a washing machine under the stairs by where the family was building another cinder building (barely in the first phase). On P-days (Preparation days which were Mondays), we would hang our wet clothes on the wire clothesline to dry in the sun, often leaving our socks partially crusty and faded and our clothes as a whole slightly dusty. When it would rain, we would seek drying alternatives in other places, suspending clothes on hangers in the shower or on the sheltered hammock (although the humidity wouldn’t allow them to dry entirely, just mostly). We were somewhat fortunate to have a washing machine even though we had to fill it with a hose that would occasionally spray dirty water. When that happened, it would take an insane amount of time to drain and clean out, and even longer in order to fill twice for one rinse cycle. And both of us combined had a lot of clothes to clean.

Washing clothes was a nuisance but you had no other choice when you’re always sweaty and dusty. We only had a week's worth of clothes to wear so you didn't want to skip the one day per week you could wash them. We would take our clothes to a laundromat were one nearby but we did not have that convenience in my first area. Even then, some missionaries would prefer to save the fifty or so pesos by washing their clothes by hand but we really didn’t have the time to do that on P-day with shopping and meetings going on. (See "P-Days, Peceras, and the Zone")

Getting back to my first impressions of the place, one of the neighbors who lived in front of us came to say hi as we pulled up. He was also a member but didn’t attend church for a number of reasons. He came over and said some things to Elder Howard. Then Elder Howard turned around to talk to the family while the neighbor continued to talk to me. All I could do was look at him like, “Sorry but I don’t know what you just said” and I tried to say, “I don’t know much Spanish”. He literally almost fell backward because he thought I was Hispanic! He actually was freaking out in disbelief. He turned to Elder Howard and said a few things but I only picked out some words including “war” and “don’t tell him”. I wasn't completely incompetent.

Comments