29. P-Days & Peceras

- L Rshaw

- Sep 9, 2019

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 13, 2022

"A person buying ordinary products in a supermarket is in touch with his deepest emotions"

--- John Kenneth Galbraith (Canadian-American Economist; 1908 - 2006)

The closest thing we had to a day-off as a missionary of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints was a "P-Day" otherwise called "Preparation Day". Even then, it wasn't much of a day-off because we still had errands to run. Nevertheless, it was something to look forward to, if only to meet up with mission buddies and email home. For me, it was the one day of the week where I didn't have to feel so much like a responsible adult in a white shirt and tie and more like a normal young guy who likes to have fun with friends.

Click to Navigate (Table of Contents):

P-DAY

As I've mentioned before, every Monday was our Preparation Day or "P-Day" (Día de preparación in Spanish). As you could imagine, P-Days were the day to get all the chores done to free up the rest of the week. We'd wake up just as early as any other day, at 6:30. We'd fill up the washing machine under our stairs with the hose, throw in some powdery detergent, run a load, hang it out to dry on the clothesline, and repeat which took a lot of time between the two of us (See "1st Area: Monterreal, Rio Bravo"). Besides laundry, we'd usually go shopping at the Soriana which was about a 20-minute walk (.7 miles) from where we lived taking into account having to carry home in our hands and backpack whatever we bought. Considering how scrawny I was, that was the worst part of the day. It made it even worse when the dirt was mud and we had to be wary of slipping into puddles on the unpaved path home with heavy bags in both hands.

Just across the road from the Soriana was a cybercafe called, "La Esquina de Queso", or in English, "The corner of cheese" (Because, why not?). Before burdening ourselves with groceries, we'd usually go to the cybercafe to email home (This was before weekly phone calls home were allowed). In our mission, we were allowed a maximum of 2 hours to write home and to email the Mission President on our personal progress and goals, and so forth. Many people also wrote friends but almost nobody emailed me besides my family and President Morales so I'd have the whole two hours to write a lengthy email about the happenings of the week and to send pictures. Compared to some missionaries, I wrote novels. Seems like things haven't changed much since.

As I've mentioned before, missions of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints are organized into smaller manageable groups like a Russian nesting doll. The fundamental unit is the companionship of two assigned companions. Then you have Districts that are made of three or four companionships. Then you have a Zone which is about two or so Districts. Respectively, there are those in charge of their flock: "Senior" companion, District Leader, and Zone Leaders all of which are fellow missionaries assigned by the Mission President.

PECERAS

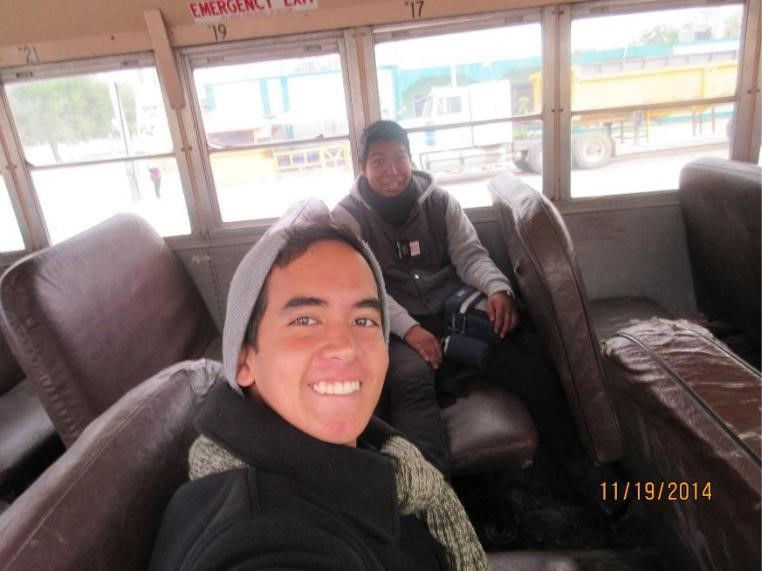

Sometime in the afternoon (at least during my time in Rio Bravo) every P-Day, we'd be instructed by our District Leaders or Zone Leaders at the church building (See "Mission Administration"). In order to get there, we had to take the bus. The buses were called peceras (which is actually Spanish for "fishbowls" or "fish tanks") and cost eight pesos per ride (equal to about forty U.S. cents). The whole frame of the bus shook and sent us bouncing off our seats every time it hit a pothole of which there were typically many. It was wise to hold on for dear life. I can’t recall seeing speed limit signs anywhere ever.

Certainly, there was no maximum occupancy either. The goal of a bus driver was to get paid as much as possible and that came from cramming in the customers. He kept a coin stand on his dashboard and peso bills clutched in hand as he operated the steering wheel; he wasted no time dishing out the change in order to circulate new passengers. He never forced anyone on board but if the passengers chose to risk it, he wouldn’t stop them from stepping on each other. One time we had to get off through the emergency exit door because it was impossible to squeeze through the crowd; the driver didn’t have the patience for that. We were literally standing back to back with backpacks on, shoulder to shoulder, one hand on the handlebar on the roof with no room to breathe; there was no way we could make it to the front door. And unless you made your voice heard past the noise and the mass, you ran the risk of missing your stop as the driver zoomed as fast as possible through the streets. Some passengers had to resort to clinching onto the iron bar above their heads which at times was loosely attached. Thankfully, most of the time people were very courteous to the elderly, women, children, and handicapped.

Other times, people would be literally half hanging out the open bus doors. At least once, I saw a young person rest himself across the wide dashboard itself like it was a bunk bed. If you did get a seat, the hard-brown leather graffitied with sharpie could be torn with the sponge stuffing all but gone, or the seat itself unattached like a couch cushion on a bench that slid off with the abrupt turn of the pecera. If there was a bump in the road, you might find yourself holding the seat beneath you like a motorcycle passenger and still be sent a couple of inches into the air with the cushion in hand only to break the fall, like you would if you were to go tubing on a lake. You'd look around at the other passengers and you'd all have the same look of disbelief in your eyes, wondering if you should be laughing or crying at how ridiculous the ride was. Other seats were hard gray plastic and uncomfortable even though you were less likely to go flying in them.

The interior of the pecera was mostly decorated with colorful depictions of the virgin Mary and other catholic decor and old advertisements. Many looked worn and homemade like they had been permanently plastered there for years with outdated phone numbers. Some tin floors would have holes rusted through them only about the size of coins; still, I feared I’d drop a pen or peso through the floor but I never did to my knowledge (I'd occasionally hold my hand over my shirt pocket just to be safe). You could see the moving ground passing beneath us at times like a conveyor belt. The decay in the floor was minuscule and ran no risk of breaking. The peceras in Rio Bravo were probably the worst in the mission; that is to say that there were better peceras out there.

Sometimes the peceras came with entertainment. In Reynosa, you could get a clown or two hopping on board just to do some stand-up comedy (which honestly was hilarious and well-executed) for some spare change. If not clowns, then you’d get the occasional students improvising a rap, sometimes including us in the rap. They were pretty talented too. Whatever the case, no one ever objected. Anyone could make an announcement or show they wanted too and no one would stop them. It was like a standup comedy club on wheels. Or a mobile caravan of street performers and buskers. Who says no to a free show? If I had some spare change, I'd usually give them their due for a good act.

The music of choice was ear-banging reggaetón or banda (a lot of trumpet and accordion). It all sounded the same. The combined music and crowd of the pecera made it almost impossible to hear the guy next to you. You’d have to shout to be heard. The peceras were assigned routes and would stop literally anywhere the passengers asked along the way. All you had to do was shout, “Baja” (Bah-hah), literally translating as “down” or tap a metal coin against the metal roof or glass window and the bus would decelerate throwing everyone forward again. You’d need to literally jump off the platform before he sped off again, only occasionally bumping your shoulders against the door in the process.

Most buses were numbered or had the neighborhoods painted on the window or windshield. If you weren’t careful, the wrong pecera could take you in the wrong direction. That’s why it was always good to know how to get where before getting on a bus, no matter where it said it would take you. My companions usually knew which to look for based on the neighborhood name on the window. It never hurt double-checking with the drivers if he were to pass through your designated neighborhood before getting aboard. In our case, we needed to get to the center of Rio Bravo for our P-Day meetings.

ENTERTAINMENT

After our training meetings, our Zone usually played soccer (fútbol which was far too advanced for me to even compete in), or volleyball on the basketball court behind the chapel. The net itself was very long and skinny so it was easy to accidentally hit it under the net. We'd play for a few hours until it got dark but even then there was a streetlight or two, that were more like floodlights, that illuminated the court (if we had the key to turn it on). A lot of neighborhood kids and other Ward members liked to play with us. Some of the Elders even had their own red and black striped jerseys. Elder Johnson had one that said, "Juanson" on the back.

There were a handful of times we played

basketball in a park in the middle of Rio Bravo and got to meet a few neighborhood kids that way. The only time I played, I hit my index finger on my left hand the wrong way and sprained it. That was the only time I had to go to the hospital, not only on the mission but in my whole life up to this point. I had it wrapped, got some pain medication for it, and it got better within a week or two. That's why I don't like playing sports! I always get hurt! Remember what happened to me in the MTC? I don't know if the photo above does it justice, but you can see it's a little purple and swollen so much that I can't bend it.

After playing, we'd almost always go back to our Zone Leaders' house (which was quarter-mile south of the chapel) for a sleepover because, by that time in the night, there were no peceras or taxis that could take us home until early the next morning. There wasn't really enough room but we did our best. We'd get the extra mattresses out, and someone would usually sleep on the couch. I'd usually offer to buy everyone a Dominoes pizza (since they delivered) so long as someone else ordered since I didn't want to try speaking Spanish over the phone. It became so routine that I dare say we became loyal customers of theirs. One time, our pizza came with personal sticky note messages that translate as, "Dominoes surprises you!" and "Be Happy". I don't know what they meant by that since there was nothing unusual with the pizza but it was a fun "extra-mile" gesture. Elder Martinez was often the one to order the pizza. When they'd ask for a name they usually couldn't understand "Elder" (since it's an English word) but one time, the pizza receipt came back with the name "Elder Feliz" which means "Happy Elder" instead of "Elder Martinez". With warm pizza in my stomach and an occasional large bottle of soda, you could say that!

In many ways, the Zone is like a family in the mission. Being together was just as much fun as it was instructional. After a long week of just me, my companion, and strangers on the street, it was a treat to get together to play, laugh, eat, and just see how everyone was doing. I think that the general public sometimes forgets that missionaries are just normal people, young kids most of the time, that still have feelings and life aside from preaching.

Comments